Black Sound and Silence: 1960s Avant-Gardes and Their 21st-Century Reverberation

by Andrew Hansung Park, Curatorial Fellow

The MCA DNA Research Initiative is a multi-year curatorial program, supported by the CHANEL Culture Fund, that invites early-career curators and writers to the museum for interdisciplinary research projects related to the institution’s collection. Focused on the intersection of visual art and performance, this initiative surfaces overlooked art historical narratives within the organization’s history while foregrounding the cross-disciplinary ethos that has been integral to the museum since its founding in 1967.

Signifyin’ monkey, stay up in your tree

You are always lying and signifyin’

But you better not monkey with me.

—Oscar Brown Jr., refrain from “Signifyin’ Monkey” (1960)

As the story goes, a monkey tells a lion about some disrespect that he’d heard from an elephant, who had insulted the lion’s family. Enraged, the lion rashly picks a fight with the much larger elephant, leading to a pretty lopsided affair. After the lion is thrashed, the monkey laughs and reveals his trick—he’d made up the entire situation in order to subvert the so-called king of the jungle. Oscar Brown’s playful and soulful rendition of the classic African American folktale repeatedly calls for the monkey to stop signifyin’ in its refrain. In other words, each refrain is a futile attempt to silence his skillful rhetoric. For ultimately, at the end of the song, the monkey escapes the lion’s revenge with yet another verbal trick and scampers away, free to keep monkeying with his foes.[1]

And what is “signifyin’”? It’s an informal, everyday practice of transforming an old idea into a new one by cleverly altering certain aspects of it. From ironic wordplay to jazz improvisation and hip-hop sampling, signifyin’ has been especially important in African American culture as a trope that branches off from the conventional language of the dominant white culture. That’s why the g is dropped in signifyin’, amounting to a distinctly spelled word that embodies its own definition and continues to accumulate more meanings as it’s applied to different contexts. In particular, the character of the signifyin’ monkey had an outsized presence in Black music of the mid-twentieth century, underscoring how essential sound is to the practice.

The literary critic (and longtime host of the TV show Finding Your Roots) Henry Louis Gates Jr. theorized the practice within intellectual circles in the 1980s by elaborating on an older idea by the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, in which a signifier (an observable component, or “sound-image”) and signified (the unobservable, abstract concept to which a signifier refers) work together to make communication possible. Signifyin’ plays with this convention—the signifier may refer to one signified idea, or maybe another, despite its apparently singular form. Gates likens this disruption in conventional communication to “stumbling unaware into a hall of mirrors,” as a signifier’s meaning multiplies yet sonically disappears. Signifyin’ replicates Saussure’s sound-image, minus the sound.[2] Granted, Gates’s poststructuralist formulation is one particular take on how to creatively reuse signifiers. What will be crucial here is a broader recognition of how the dynamic of Black sound and silence, not just language, branches off from the dominant culture, building new relationships to representation and meaning. This critical branching activity has always been right at the center of white discourse about art, yet it’s long gone unacknowledged.

Sound and silence are two sides of the same coin; they need each other to exist. Because of how difficult it is for the human mind to track multiple sounds at once (try to closely follow the melody, accompaniment, and bassline of Brown’s song all at the same time, and you’ll quickly realize how confusing that gets), one sound here often results in a silence elsewhere. We undoubtedly live in a chaotic world where sonic phenomena continuously compete with each other for our attention. The two interdependent categories continuously expand into and constrict each other, drowning the other out. Just as much as sound, silence also has an immense communicative power, in that its seeming emptiness has appeared extremely inviting to countless musicians and artists who have used the concept to their own ends. Most importantly, the word “silence” has a functional flexibility, as both a noun and a verb, to signify totally different things: silence as an erasure, an exclusion, authorial restraint, a social construct, an impossibility, or even a presence.

To reflect on the lyrics of Brown’s refrain is to realize how potent the dynamic of Black sound and silence can be in critiquing the racialized way that power exists. Using art in the MCA’s collection, we can see two related episodes in the histories of art and experimental music as they struggled to accommodate the achievements of Black musicians. The legacy of the Black sonic avant-garde of the 1960s has only recently been taken up by the mainstream art world, which is now attempting to undo its initial erasure in history. So even if signifyin’ might appear to us today as a dated concept that perpetuates certain racial stereotypes, its lessons about altering convention resonate with the lessons of avant-garde sonic art that thrived in the 1960s and powerfully echoes into the present day, always awaiting a fuller cultural reckoning.

I

1. Two Black Paintings

In the MCA’s collection are two black paintings, similar in some ways but different in most. Each tells a story about how their makers understood blackness as a color and a concept, and how they engaged with the legacy of Black avant-garde music.

The first painting is Ad Reinhardt’s Abstract Painting (fig. 1) from 1962, a square of subtle colors that can only be fully perceived after prolonged viewing. As your eyes adjust to the overall darkness, a horizontal band of warmer black comes to the front, as a vertical band of blue-black crosses it in equal length. The emergence of a grid-like pattern of squares is powerfully captivating, especially when you consider the fact that Reinhardt spent the last fifteen years of his life on these ultimate paintings. As emblems of authorial silence, the ultimate paintings exhibit no trace of Reinhardt’s hand. In his unwavering commitment to black as a pure non-color, he obsessively returned to creating more and more of the last paintings that were possible under the collapsing umbrella of high modernism. For him, there was no other option.

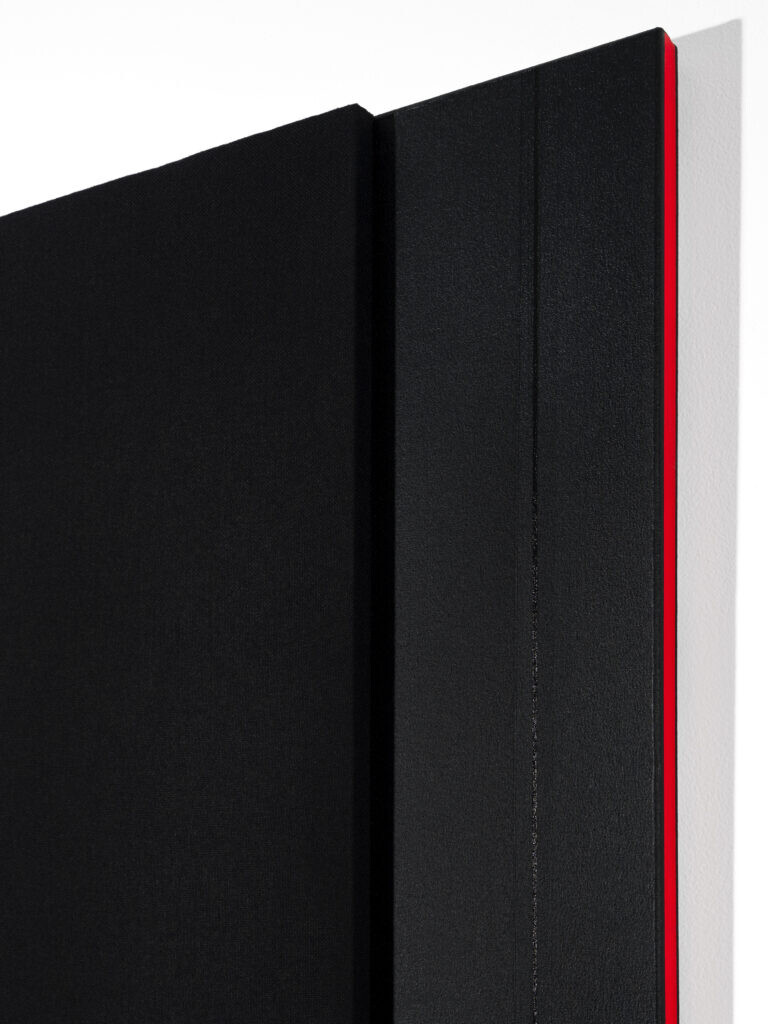

The second black painting is Jennie C. Jones’s Deep Tone with Double Bar Line (fig. 2) from 2014. What appears to be a straightforward rehearsal of monochrome painting, copied from the foreclosed past of modernism, turns out to be a surprising combination of elements. Jones’s painted canvas forms the support for yet another painting-like object, a black acoustic panel that protrudes conspicuously from the wall and shatters any notion of medium-specific flatness. Commonly found in music practice rooms and studios, acoustic panels are designed to absorb and dampen ambient noise in order to create a quieter, more contemplative environment. Her use of silence, one that can be physically experienced when your ear is pressed close to the panel, is a comment on how the impact of radical Black sound has been silenced in mainstream art histories of minimalism and conceptualism. On either side of the panel, which dominates the center of the composition, there are intricate lines made apparent by their different textures. The upper and right edges of the canvas are the loudest, though, because they’ve been painted a searingly bright scarlet (fig. 3). This hidden pop of color—referred to in the title as a “double bar line” (as in musical notation), though in other works Jones calls it a “reverberation”—can be directly seen when Deep Tone is viewed from the side, or it can be indirectly seen as a halo-like reflection against the wall.

Figure 3. Jennie C. Jones, Deep Tone with Double Bar Line (detail), 2014. Acoustic absorber panel and acrylic paint on canvas; 48 × 48 × 3in (121.9 × 121.9 × 7.6 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Gift of Marilyn and Larry Fields, 2023.64. Photo: Shelby Ragsdale, © MCA Chicago.

What these two works have in common is the type of perceptual demand they make on their audiences. Reinhardt and Jones want to foster rigorous contemplation of their paintings, both of which were executed as part of a larger series of matte black paintings. Most significantly, however, it’s their respective encounters with 1960s free jazz that I’d like to highlight. In particular, their unique interactions with the composer-pianist-poet Cecil Taylor reveal the artists’ wildly different understandings of what “black” really is.

2. “Don’t you understand?”: On the Phone with Cecil Taylor

In 1967, the journal arts/canada, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and Bell Telephone Company organized a conversation between seven artists and critics of diverse media who were calling in from New York and Toronto. The panel was tasked with discussing what the word “black” meant to them “as spatial concept, symbol, paint quality; the social-political implications of black; black as stasis, negation, nothingness and black as change, impermanence and potentiality.”[3] Despite the fact that the Black Power movement was in full swing at the time of the conversation, most of the panel focused on the context of the high art establishment, of which Reinhardt’s paintings were emblematic.

At the New York location, Reinhardt sat next to Cecil Taylor, who was the only Black person on a panel that was otherwise comprised of six white men. A quick reading of their body language captured in photography of the event tellingly reveals the social dynamic of the hour-long conversation. Reinhardt, ever the outspoken purist, leans into the microphone to hammer out his own viewpoint, while the frustrated Taylor, shielded by a pair of thick sunglasses, leans back to look at the ceiling. The October 1967 arts/canada issue that transcribed the conversation in full was published as a tribute to Reinhardt, who passed just fourteen days after the event. The Minimalist painter Frank Stella similarly described that dynamic in his tribute to the late artist, writing, “[Reinhardt] said what was right about what he did and what was wrong about what other people did. People tolerated his work and polemics, but nobody liked it.”[4]

Over the course of the conversation, Reinhardt emphasized that black was crucial for him not as a color but as a neutral absence of color, one that was so non-referential so as to eliminate all personal expression and social content from his ultimate paintings. Because he was so insistent in repeating this viewpoint, the conversation’s overly aesthetic parameters could’ve completely silenced the only Black voice on the panel, were it not for Taylor’s rhetorical power. Initially, the musician related black to silence, musing that “silence may be infinite or a beginning, an end, white noise, purity, classical ballet; the question of black, its inability to reflect yet to absorb.”[5] Taylor’s poetic intervention, however, would develop into a harsher criticism of Reinhardt’s universalizing formalism, however, as the pianist posed a series of fiery questions:

Reinhardt: I suppose in the visual arts good works usually end up in museums where they can be protected.

Taylor: Don’t you understand that every culture has its own mores, its way of doing things, and that’s why different art forms exist? People paint differently, people sing differently. What else does it express but my way of living—the way I eat, the way I walk, the way I talk, the way I think, what I have access to?

Reinhardt: Cultures in time begin to represent what artists did. It isn’t the other way around.

Taylor: Don’t you understand that what artists do depends on the time they have to do it in, and the time they have to do it in depends on the amount of economic sustenance which allows them to do it? You have to come down to the reality.[6]

While Reinhardt’s belief that society follows art is certainly a powerful one, Taylor expressed a more grounded perspective that art is subject to the same socio-economic conditions as any other human activity.

This rare encounter between two leading lights of the fine art and experimental music worlds has only recently been brought back into the spotlight, with the theorist Fred Moten detailing the incommensurability of their perspectives in an article in 2008.[7] Indeed, Taylor’s lived experience of blackness was subject to a profound erasure when the art critic Barbara Rose didn’t include their exchange in her excerpt of the conversation, titled “Black as Symbol and Concept” and published in Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt in 1975. This temporary silencing, between the 1970s and 2000s, demonstrates just how urgent the sonic legacy of the 1960s Black avant-garde is today for completing an understanding of this avant-garde’s reverberations in contemporary art—its view of history and culture, its critique of constructing blackness as an absence, and its pluralistic recognition of many possibilities within signified forms.

3. Unit Structures and Neomodernism

Just one year before the arts/canada conversation, in 1966, Taylor had released the album Unit Structures, a landmark recording in the expanding world of free jazz. Accompanying the collection of original compositions were liner notes in the form of a critical essay/prose poem penned by Taylor himself. Given the fact that the vast majority of liner notes in the 1950s and early 1960s were written by paid critics, almost all of whom were white, Taylor’s writing posed a challenge to a music industry that was accustomed to speaking on behalf of its Black musicians.[8] Titled “Sound Structure of Subculture Becoming Major Breath/Naked Fire Gesture,” Taylor’s writing represented the emergence of the jazz composer as an intellectual capable of sophisticated cultural and political commentary. Rather than portraying himself as just an entertainer in pre-bebop fashion, he demonstrated his commitment to speaking out against the overdetermination of Black meaning by white conceptual frameworks. Indeed, in the essay/poem, Taylor “theorized the place of improvisational musicmaking in U.S. artistic culture . . . and how it was a critique of U.S. history, culture, and power relations therein.”[9]

The album’s title track, “Unit Structure/As of a Now/Section,” is an explosive combination of improvisations by Taylor and his bandmates, collectively called the Cecil Taylor Unit.[10] The repeated use of the word “unit” to describe his music points to a systematic, mathematical way of understanding sound that creates a foundation for the spontaneous and complex techniques that characterize his playing. “Unit Structure/As of a Now/Section” begins quietly but with much rhythmic tension, with Andrew Cyrille drumming a simple pattern on the tom-tom while Taylor plays the inside of the piano in an equally percussive way. Alto saxophone, trumpet, bass clarinet, and bowed basses join in quick succession, forming a multi-voiced conversation in which each instrument skillfully responds to the others. It’s a drama of all of these differing voices, positioned next to and on top of each other, and they combine to form a variegated whole that’s greater than the sum of its parts.

The contemporary artist Jennie C. Jones enacts her own dialogue with Taylor’s Unit Structures in her identically named monochrome paintings of 2019–20. Rather than argue with Taylor like Reinhardt did, Jones uses plum-red, sound-absorbing panels to juxtapose an eerie quietude with the cacophony of compositions like “Unit Structure/As of a Now/Section.” The making of her Unit Structure paintings was accompanied by deep research into Taylor’s performance practice, even if all of the notes about his music that she compiled are stripped away in the final artworks. Just as she did with the seemingly non-referential Deep Tone with Double Bar Line, Jones lets her paintings exist as formal objects and reflects on how the grand narratives of modernism have been constructed.[11]

By layering the vocabularies of the monochrome (as practiced by painters like Reinhardt) and free jazz, Jones presents a revisionist project that pairs the twin developments in 1960s New York of a predominantly white visual avant-garde and a predominantly Black sonic avant-garde. As evidenced by the arts/canada conversation, these contemporaneous developments have historically struggled to enter into a cooperative, productive dialogue. She describes the strongly historical bent of her art as “neomodernist,” meaning that it’s a reflection on modernism through the critical lens of postmodernism.[12] In other words, while her acoustic paintings may appear to simply rehash the formal elements of modernism, they are also imbued with the postmodernist debates about identity politics with which Jones came of age in the 1990s during her schooling at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Rutgers University. The Unit Structure paintings pay homage to Taylor’s modernist achievement while also questioning the gaps in mainstream art history that have silenced the crucial contributions of Black sonic artists.

II

1. “Bird in Cage,” or, the Racialization of Experimental Music

No discussion of silence in contemporary art can be complete without reference to the composer John Cage, whose work in the 1960s tended to overshadow new developments in jazz, as far as the mainstream art world was concerned. His conception of silence, partly born out of his experiences with South and East Asian philosophy and aesthetics, is significant for understanding silence as an artistic strategy precisely because it rules out the very existence of silence; in a world full of constant activity, sound is always present. According to Cage, even an anechoic chamber, a meticulously soundproofed room where all echoes and external noise are eliminated, is unable to achieve complete silence.[13]

Figure 4. Thomas Demand, Labor (Laboratory), 2000. Chromogenic development print and Diasec; 71 x 105 1/2 in. (180.3 x 268 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Gift from The Howard and Donna Stone Collection, 2002.18. Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

The German photographer Thomas Demand’s Labor (Laboratory) (2000; fig. 4) represents Cage’s claim by demonstrating how silence can quite literally be a fabricated, human construct. Following his usual process, Demand began this work with an original photograph of an anechoic chamber built by the automobile company BMW and translated it into a three-dimensional, life-size paper model. This model was then photographed again to become Labor (Laboratory), giving the final image an uncanny, simulated feel. The socio-historical conditions of silence—precisely what Taylor emphasized—are also highlighted by Demand because of how the origins of the anechoic chamber were inextricably linked to warfare, as BMW used this technology to run acoustic tests on Nazi vehicles.[14]

The necessarily social and uncontrollable nature of silence led Cage to focus on noise and indeterminacy in much of his sonic art. Take, for instance, A Dip in the Lake: Ten Quicksteps, Sixty-two Waltzes, and Fifty-six Marches for Chicago and Vicinity (1978; fig. 5), which is a large map that’s been crisscrossed with colorful pen lines that connect over four hundred Chicago-area addresses. Cage grouped the specific locations into groups of two, three, and four to correspond to the typical time signatures of each titular dance or musical genre, following a chance-driven process that he had previously applied to New York and can be adapted to other cities as well.[15] A Dip in the Lake invites us to traverse the expanse of Chicago and listen to the people, transportation, weather, water, and animals that contribute to its unique urban soundscape.

Figure 5. John Cage, A Dip in the Lake: Ten Quicksteps, Sixty-two Waltzes, and Fifty-six Marches for Chicago and Vicinity, 1978. Felt-tip pen on map; Framed: 55 3/4 × 43 3/4 in. (141.6 × 111.1 cm), Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Restricted gift of MCA Collectors Group, Men’s Council, and Women’s Board; and National Endowment for the Arts Purchase Grant, 1982.19. Photo © Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago.

This classic discourse of Cagean silence, which was consolidated and popularized in the 1960s, shows its limits when it has to reckon with jazz. Indeed, an irony emerges, in that Cage’s conception of silence attracted considerable attention from the art world and tended to drown out contemporaneous developments in improvised music, Taylor’s Unit Structures included. So even though both Cagean indeterminacy and jazz improvisation may share an underlying desire to introduce spontaneity into musicmaking, these two practices remained mostly isolated from each other in their own cultural spheres.

The musicologist and composer George Lewis calls this uneasy relationship in postwar experimental music the “Bird in Cage” dynamic (“Bird” being the nickname of the bebop saxophonist Charlie Parker), in which many white composers who used chance-related strategies in the US and Europe denied the potential impact of Black improvisation on their own music.[16] As a matter of fact, Cage didn’t view jazz as “serious” music on the same high level as classical music, and he criticized improvisation as “playing what you know,” claiming that it “doesn’t lead you into a new experience.”[17]

According to Lewis’s reconstruction of the historical timeline, however, bebop and its innovations in musical spontaneity precede Cage’s own turn to indeterminacy by approximately a decade. As a result, the musicologist argues that the 1940s emergence of bebop improvisation posed a new challenge to the existing musical order that needed to be answered. Cage’s response—a turn to indeterminacy and silence—should then be seen as a successor to (or even a subset of) improvisation. The Chicago-born composer Anthony Braxton summed up the “Bird in Cage” dynamic in an even more confrontational fashion: “Both aleatory and indeterminism are words which have been coined . . . to bypass the word improvisation and as such the influence of non-white sensibility.”[18]

2. The Freedom Principle

There is one particular section of the map in A Dip in the Lake, particularly overrun by Cage’s dense lines, that was home to a collective that redefined the possibilities of experimental music everywhere. In 1965, the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) was founded on the South Side of Chicago in order to host group discussions about aesthetics and career logistics, manage performance venues, and promote original compositions (rather than old jazz standards)—all in the name of Black self-determination.[19] The AACM came together at a time when the civil rights movement had already swept across the country, which then led to the Black power movement and its artistic counterpart, the Black Arts Movement. The previously mentioned Lewis and Braxton have both been key members of the AACM. Its performances took the conventions of jazz and exploded them, pushing the genre into the avant-garde realm of experimental music on account of its extreme improvisations and unorthodox instrumental techniques.

The still-active collective, its relationship to the visual art of the neighboring African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists (AfriCOBRA), and its abiding importance to other artists working today were the subject of the MCA’s 2015 show, The Freedom Principle: Experiments in Art and Music, 1965 to Now.[20] In many ways, the show was meant to overcome the “Bird in Cage” problem. Cocurated by Naomi Beckwith and Dieter Roelstraete, The Freedom Principle was extremely loud, as far as art exhibitions go. And this was fitting—the show was very much about overlooked South Side musicians and artists making noise and claiming their own space in the cultural landscape of the United States. Periodic sonic activations of artworks and musical performances animated the MCA’s galleries over the course of the show’s run, as it charted an alternative history of sound from the 1960s onward that can’t be contained by the canonical framework of Cagean silence.[21]

Figure 6. Installation view, The Freedom Principle: Experiments in Art and Music, 1965 to Now, MCA Chicago, July 11–November 22, 2015. Photo: Nathan Keay © MCA Chicago.

For example, the sculptor-composer Terry Adkins’s Native Son (Circus) (originally designed in 2006/posthumously constructed in 2015) was a floor-bound cluster of magnetized cymbals that filled the museum with the overwhelming sound of clanging metal (fig. 6). Loosely inspired by the legendary story of the drummer Jo Jones throwing a cymbal at a young Charlie “Bird” Parker, Native Son (Circus) was thoughtfully placed in front of another black acoustic painting by Jennie C. Jones in two parts. Collectively titled Vertical into Decrescendo (dark) (2014), her work actively dampened the percussive cacophony emitted by Native Son (Circus), emphasizing the interconnectedness of The Freedom Principle’s multisensory environment.

3. Postlude: Escaping the Cage

On the last two days of The Freedom Principle’s run at the MCA, the performance artist Pope.L presented Cage Unrequited, a twenty-five-hour reading of John Cage’s classic 1961 book Silence: Lectures and Writings. Previously performed in New York in 2013, Cage Unrequited featured over 200 invited people getting up on stage to solemnly read (or sit in silence and not read) the composer’s text into microphones. The marathon performance had the feel of a rehearsal, in that the MCA’s theater was casually furnished with couches, throw pillows, and colored lights, and the audience was free to come and go.[22] Pope.L’s turn on stage began and ended with him reading Silence, but the central part of his turn was a lecture on the underrecognized composer Julius Eastman.

By inserting a lecture on Eastman into an otherwise reverential event centered on Cage, Pope.L deliberately changed the tenor of the entire situation. Eastman got his start in the 1960s as a classically trained pianist, though his own music and performance practice would go on to incorporate minimalism, pop, jazz, and his own brand of theater. His identity as an openly gay Black man surfaced not only in his own compositions but also in his performances of other composers’ work. As Pope.L narrated in the lecture, one such performance of Cage’s theatrical Song Books happened in 1975 when Eastman undressed his boyfriend and attempted to undress his sister on stage. To say the least, it was a rebellious act to signify on the famous, older composer’s songs in such a way. This overt expression of sexuality left Cage (who preferred to be discreet about his own queerness) feeling insulted and the wider classical music establishment feeling scandalized, which only further reflects signifyin’s fondness for aggressively destabilizing social norms.

For Pope.L, Cage Unrequited was about “the impossibility of absenting oneself from a work one makes—and how irritating and fascinating Cage found the whole thing.”[23] As much as Cage tried to erase all ego from his music (following the principles of Zen Buddhism), he was powerless to stop Eastman from asserting his queerness through Song Books. Just like The Freedom Principle did for jazz, Pope.L’s lecture charted an alternative historical trajectory for Black sound and silence in classical music. His intervention emphasized the centrality of the Black avant-garde, just like how Jones’s Unit Structure paintings acknowledge Taylor’s passionate challenge to Reinhardt’s exclusionary understanding of abstraction. Through Cage Unrequited, it was as if Eastman couldn’t be erased from history, despite the fact that he died in poverty and obscurity in 1990. Twenty-five years later, Pope.L made sure that Eastman burst through the Cage, now free to make some real noise.

Notes

1. Other renditions of the story (musical or otherwise) have been performed by the likes of Cab Calloway, Nat King Cole, Chuck Berry, Johnny Otis, Rudy Ray Moore (via his character Dolemite), and Schoolly D.

2. Note that Gates spells it as “Signifyin(g).” Henry Louis Gates, Jr., The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African American Literary Criticism (Oxford University Press, 1988), 44.

3. “Black,” arts/canada 113 (October 1967): 1–19.

4. “Black,” arts/canada, 2.

5. “Black,” arts/canada, 5.

6. “Black,” arts/canada, 13.

7. Fred Moten, “The Case of Blackness,” Criticism 50, no. 2 (Spring 2008): 189–99.

8. Amiri Baraka (then known as LeRoi Jones) analyzed this general phenomenon in his essay “Jazz and the White Critic” (originally published in 1963), republished in The Jazz Cadence of American Culture, ed. Robert O’Meally (Columbia University Press, 1998), 137–42.

9. Andrew Bartlett, “Cecil Taylor, Identity Energy, and the Avant-Garde African American Body,” Perspectives of New Music 33, no. 1/2 (Winter/Summer 1995): 274–93.

10. “Unit Structure/As of a Now/Section” is the fourth track of the album. The lineup/instrumentation is as follows: Cecil Taylor, composer/piano/bells; Eddie Stevens, trumpet; Jimmy Lyons, alto sax; Ken McIntyre, alto sax/oboe/bass clarinet; Henry Grimes, bass; Alan Silva, bass; Andrew Cyrille, drums. youtube.com/watch?v=aeR3ikMrYGM.

11. Jennie C. Jones, interview by the author, March 26, 2024.

12. Terry Smith, Christoph Cox, and Victor Grauer have all written about neomodernism in diverse ways. For Jones’s own use of the term, see Huey Copeland, “First Takes: A Conversation with Jennie C. Jones,” in Jennie C. Jones: Compilation, ed. Valerie Cassel Oliver (Contemporary Arts Museum Houston and Gregory R. Miller & Co., 2015), 25.

13. The existence of complete audiological silence (as perceived by the human subject) has been disputed by various writers, artists, and composers. Suffice it to say that silence may only exist for some people with a certain set of physiological factors (e.g., those without tinnitus). During my own visit to Orfield Laboratories’ anechoic chamber in Minneapolis in 2017, for instance, I was able to briefly experience what I would call complete silence if I didn’t breathe or blink.

14. Roxana Marcoci, “Paper Moon,” in Thomas Demand, ed. Joanne Greenspun (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2005), 9–10.

15. Robert Pleshar, “Some notes on the realization of John Cage’s ‘A Dip in the Lake’ 2001-2003,” UbuWeb, accessed April 22, 2025, ubu.com/sound/cage_dip.html.

16. George Lewis, “Improvised Music After 1950: Afrological and Eurological Perspectives,” Black Music Research Journal 16, no. 1 (Spring 1996): 91–122.

17. John Cage, quoted in Richard Kostelanetz, Conversing with Cage (Limelight, 1987), 223.

18. Anthony Braxton, quoted in Lewis, “Improvised Music After 1950,” 99.

19. The definitive account of the AACM is George Lewis’s A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music (University of Chicago Press, 2008).

20. Naomi Beckwith and Dieter Roelstraete, The Freedom Principle: Experiments in Art and Music, 1965 to Now, exh. cat. (Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, 2015). Also see “The Freedom Principle,” video, posted July 16, 2015, by the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, YouTube, 12 minutes, 10 seconds, youtube.com/watch?v=7mrnFopgCrc.

21. Dieter Roelstraete, interview by the author, March 6, 2025.

22. Erik Wenzel, “Sustained Silent Reading: Performing John Cage,” MCA DNA (blog), December 29, 2015, mcachicago.org/publications/blog/2015/12/sustained-silent-reading. For a review of the 2013 New York performance, see Catherine Damman, “Anti-Oedipus: Pope.L’s ‘Cage Unrequited’,” Art in America, December 4, 2013, artnews.com/art-in-america/features/anti-oedipus-popelrsquos-ldquocage-unrequitedrdquo-59616/.

23. Pope.L, “‘The Friendliest Black Artist in America,’ Pope.L discusses humor, management, and performance,” remote interview by Jurrell Lewis, In the Studio, Art21, December 2021, art21.org/read/in-the-studio-pope-l/.

Andrew Hansung Park. Photo: Spencer Park.

Andrew Hansung Park is an art historian, composer, and violinist who researches the intersections between modern and contemporary art and the histories of sound across North America and East Asia. He is currently an art history PhD candidate at UCLA as well as a Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Andrew has worked in various roles at the Getty Research Institute, Glenstone, and the Walters Art Museum. His dissertation is a study of the improvisational art of Sam Gilliam.

Financement

The MCA DNA Research Initiative is supported by the CHANEL Culture Fund.